The Door in the Nightmare: From the Russian Revolution to Pax Americana

Click Here to read the full book for free. If you enjoy the book, please support me by purchasing it at this link.

Introduction

My first life was lived as a Russian. It was a kind of fictional life because I wasn’t born there. But my parents were born in Russia, and had to leave it because they were on the wrong side of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. My grandmother, my sweet Babushka who lived with us, told me I was Russian, and I believed her. Actually, she was misguided because her side of the family was from Ukraine. Yet the family language was Russian, a language well suited for all the stories of war, revolution, civil strife, hunger and desolation I heard in my childhood.

My real life started in Yugoslavia. At least I have a birth certificate stating as much, even though the country itself no longer exists. In Former Yugoslavia, then, it was my turn to witness war, revolution, civil strife, hunger and desolation: World War II was in progress and Yugoslavia was occupied by the Germans and bombed by everyone else. And the resistance movements that were fighting the Germans were also fighting each other.

Like Babushka, Mother turned out to be a good story teller. We learned to run from bombs into holes in the ground known as shelters, and Mom called it an adventure. And getting a bag of potatoes after a long wait on the food line she called a triumph. But when Dad disappeared for months, then showed up unexpectedly on Christmas Eve of 1943, we all called it a miracle.

My next life found me in Germany. There was no revolution or civil strife because the Germans knew exactly who they were – and started World War II to prove it. And because we lived behind barbed wire first in a Forced Labor Camp, and later in refugee camps known as Displaced Persons camps, it was clear that we were “the other.”

Review by Christine Wald-Hopkins in the Arizona Daily Star (2-6-22)

This memoir is a many-faceted gem. It’s a personal narrative in lyrical prose in sometimes-harrowing situations, a travelogue embedded in history and politics, a lively conversation sparkling with literary allusion, and a no-holds-barred political op-ed.

Born in 1938 to Russian émigrés, former UA Russian Assistant Professor Galina De Roeck has lived in Yugoslavia, Germany, Morocco, Australia and the U.S.

Her early life was marked by fear and flight — the family’s Belgrade apartment bombed, fleeing armies in WWII, surviving a displaced person’s camp in Germany. “White” Russians, they couldn’t return home to a Stalinist USSR after the war, so they emigrated to Morocco. Seeing the revolutionary writing on the wall, then, in Morocco, they left behind their privileged existence there for a life of privation in Australia. Marriage brought her to the U.S. As De Roeck tells it, her mother’s drive, father and grandmother’s affection and the kindness of others helped her overcome cultural, linguistic and socioeconomic obstacles.

De Roeck relates an arc that begins with the terrors of war and eventually involves activism for world peace. It’s a fascinating personal and family account reflecting the upheavals of the twentieth century.

“I am foreign-born, a hybrid American, politically engineered,” she writes, “and the shape-shifter and busy-body hyphen is the secret hero of my story.”

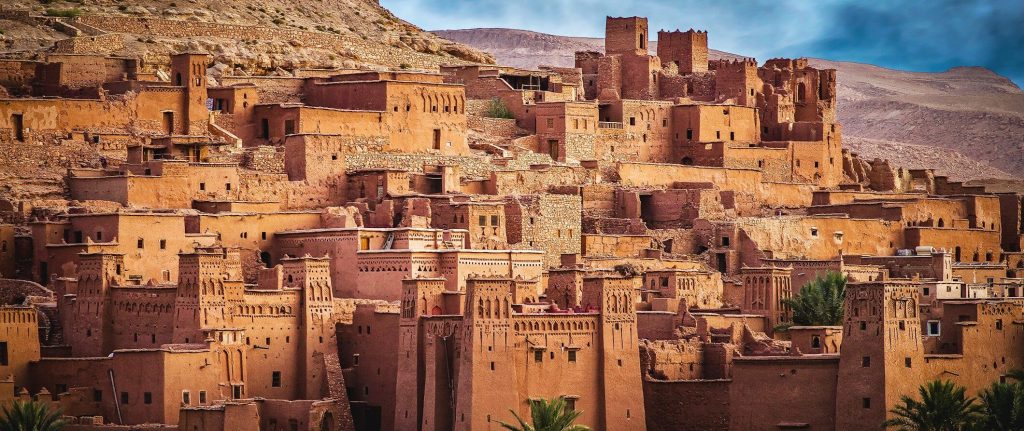

My next life lasted about nine years, and took its course in Morocco. The German language was displaced by French and Arabic. If there was hunger and desolation, it didn’t concern us. The Arabs lived in their Kasbahs perched high on bare mountain tops or in medieval sections of towns called Medinas. They only came to the European sections to clean houses or do the landscaping. My job was to learn French and to stick it out in boarding school. I managed it bye and bye and French books became a sort of home country, the source of all knowledge and understanding.

I did pick up some Arabic (you do need to communicate with the help) but it was taken for granted that that language would not disclose great treasures of knowledge and understanding. So, when evidence of rebellion, civil strife, and war broke out all around us, we were as unprepared as my family had been back in the days of the Russian Revolution.

It was time to move on again, and this took us all the way to Australia. This latest life segment proved a striking reversal of the previous one. My knowledge of Russian, Serbo-Croatian, German and French, with Latin and ancient Greek thrown in for good measure, proved useless in Australia. I was now a dumb immigrant, and it was my turn to clean other people’s houses. It wasn’t hunger and desolation exactly, but it was humiliating now that I was twenty years old, and thought of myself as pretty cool. Was it my turn to create survival stories the way Babushka and Mother had done? Or maybe take a page out of those French books, and strive for existential insight from scrubbing toilets?

Just the same, the French language was a catalyst for yet another life. A borrowed life to be sure, because it was a marriage gift from a francophone boy from Belgium named Rick De Roeck. He was a corporate brat, and his parents had been transferred to the United States. Belgium remained in limbo, and we became accidental Americans. We pursued our education and Rick got a job with General Motors, and after I got my PhD, I taught my various languages at various institutions of higher learning.

It looks like this American life is going to be my last. My children, Alex, born in California, and Muriel, born in New York, and my grandchildren Chloe and Astrid, born in Arizona, are typical monolingual Americans. We have typical middle-class problems, like which car to buy, which health insurance to pick, or how many likes we register on Facebook. Am I counting my blessings? Sure I am. Just the way my parents were counting on blessed Tsar Nicholas II to hold it together in Russia back in the day. Should I be counting on Trump or on Biden to keep it going?

But should I not know better after all those trial lives? Had I really forgotten how it was when bombs were exploding over my head and barbed wire defined my world and food was on my mind all the time because my stomach was empty? Or how they laughed at me in Australia because I didn’t know English? Or, for that matter, how imitating my elders, I rolled my eyes when the Moroccans spoke funny French?

But do war, revolution, civil strife, hunger and desolation really happen when they happen somewhere else – when they happen to others, say in Yemen? Or Afghanistan, or Iraq, or Libya, or Syria, or elsewhere in Africa or Latin or Central America? But the alarm had already rung in my head when NATO bombed Belgrade in 1999. Belgrade may have been “somewhere else” to Americans, but not to me. When I heard on NPR our missiles striking Belgrade, I became the three-year old girl crouching in a cellar in Belgrade in 1941, and it felt like I was bombing myself.

But was Milošević not the devil incarnate, and the Serbs the new Nazis? Milosevic and all the other serial killers: Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qadhafi and Bashir al Assad – and, finally, Putin, and Putin, and Putin? Really? I began to identify with the hero of the Truman Show: something was very wrong. I began to feel that I too lived in a Prison of Smiles.

I now felt the urge to put it all together and tell my story. I wanted to ring the alarm so my American kids don’t have to suffer the consequence of their blessed ignorance. And that story – my memoir, had to retrace the long struggle of stepping out of the comfort zone of received opinion: whether the pieties of my Russian family, or the complicities of colonization and empire, or the Reality Show of the American Dream.

To order, please visit https://pravpublishing.com/the-door-in-the-nightmare-from-the-russian-revolution-to-pax-americana/